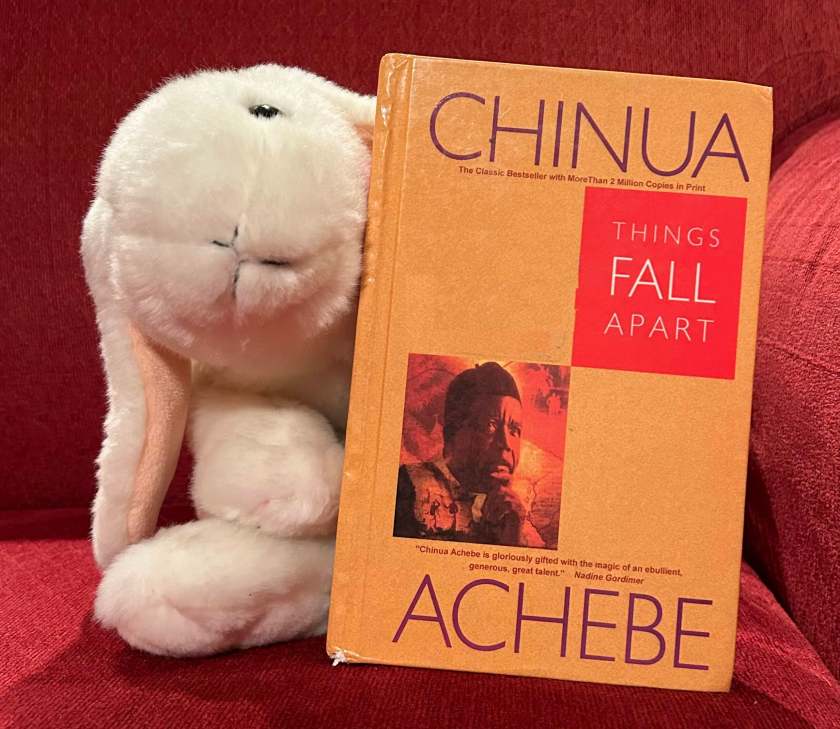

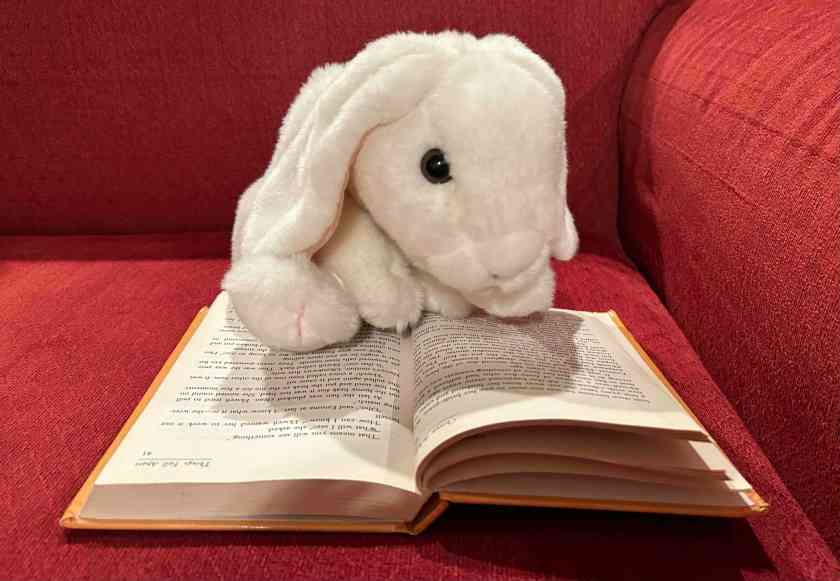

As the first review of the book bunnies blog this new year, we present to you Marshmallow’s review of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. First published in 1958, Achebe’s novel is a modern classic, and Marshmallow has read it in school.

Marshmallow’s Quick Take: If you like historical fiction books about colonialism in Africa or books that make you think or feel, then this is the book for you!

Marshmallow’s Summary (with Spoilers): Set in the Nigerian Ibo society during the 1890s, this book starts with the introduction of Okonkwo. Okonkwo is a highly-respected man in his village Umuofia. Through his victories in battle and his defeat of the Cat (a famous wrestler), Okonkwo is a powerful man. As a result (as is Ibo culture), he has three wives, many children, a successful farm, and on occasion drinks palm wine out of his first human skull. He is what is called a “strong man.” However, his success and strength is a result of fear. His drive to succeed is fueled by a fear of being similar to his father, who was a efulefu (or worthless man). Okonkwo’s father was lazy and debt-ridden; thus, Okonkwo compensates for his father’s failures by working obsessively. Luckily for Okonkwo, in Ibo society, a man is not judged by his father, but by his own merit. Eventually, his success seems cemented. Yet, he is still controlled by anxiety, fear, anger, and violence. His household, though it reflects the traditional Ibo setup of its time, is a model case of domestic abuse.

Meanwhile, a woman from Umuofia is killed in a neighboring village. To avoid war with the fear-inspiring Umuofia, this village sends a virgin girl and a young boy to compensate. For the purposes of the plot, the boy (named Ikemefuna) is most important. Umuofia doesn’t immediately decide what to do with the boy, taking several years to do so. During this, he is placed in Okonkwo’s household and soon becomes fast friends with Okonkwo’s son, Nwoye. Over time, Okonkwo starts to view Ikemefuna as a son.

But when tragedy strikes, Okonkwo finds himself in a situation that pits his “strong man” facade against his heart. And as the book progresses, Okonkwo continually finds himself at odds with the changing village. The question is, how much more can he take before he falls apart?

Marshmallow’s Review: I think reading this book is an extremely important experience that all people and bunnies should have. Chinua Achebe–the author–wrote it in simple, easy to read English specifically so it would be accessible to all; this makes it a good book for all ages and levels of reading ability. But ultimately, this book is remarkably subtle and nuanced. The author’s tone is simple and unique, while startlingly complex at the same time. The plot evolves elegantly and the author creates compelling characters that make you need to see the storyline though. Additionally, Achebe successfully grapples with and portrays issues like colonialism, racism, and toxic masculinity. This book is incredible because of the insights it gives on such topics. It also shows the reader what (some) life and culture was like in Nigeria before colonialism.

Additionally, this book’s themes are philosophically, historically, psychologically, and culturally intriguing. Throughout, Achebe weaves in the concept of facades: facades of strength, of stability, of security, of trustworthiness, of happiness, of truth. Achebe’s work is remarkable, and the astute reader will recognize and appreciate the importance of such work.

Overall, I highly recommend this book to all because it’s imperative to understand what others in the world experience and experienced, especially in a world of such divided opinions and narrow perspectives.

Marshmallow’s Rating: 100%.