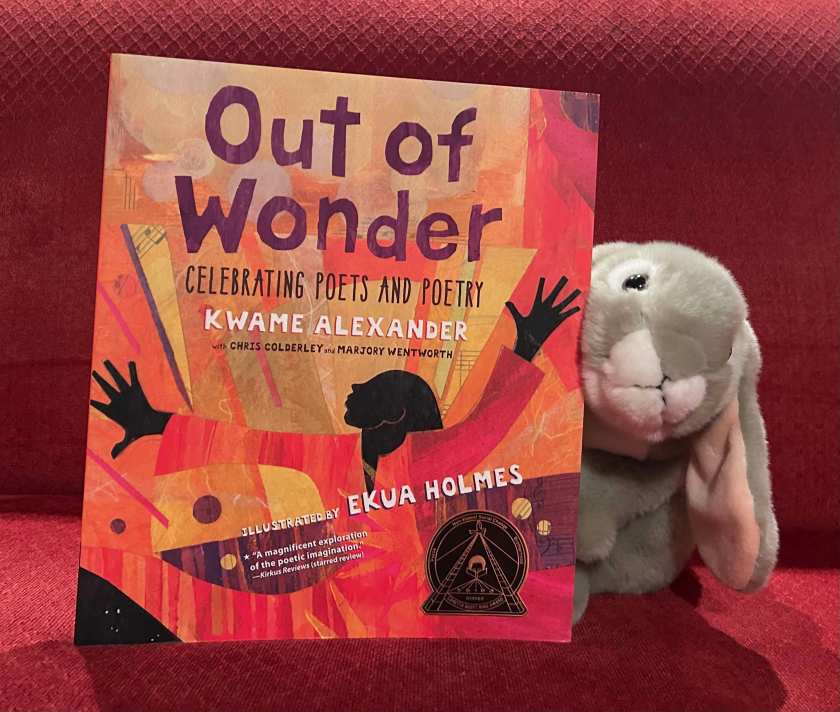

Today Sprinkles reviews Out of Wonder: Celebrating Poets and Poetry by poets Kwame Alexander, Chris Colderley, and Marjory Wentworth. Illustrated beautifully by Ekua Holmes, this poetry collection was first published in 2017.

I have already reviewed a handful of poetry books through the years for the book bunnies blog. Most of these reviews were about individual books, but earlier this year, I have also reviewed three anthologies. The book I am reviewing today can also be viewed as an anthology of sorts, though it is a very particular type. Out Of Wonder presents twenty poems from three distinct poetic voices: Kwame Alexander, Chris Colderley, and Marjory Wentworth. And each poem is an homage to a specific poet that had a significant impact on the poet writing about them.

The book begins with a preface written by Alexander, where he introduces us to the project: through poems inspired by individual poets, the three authors of this book aim to introduce to the young reader the depths and breadths of poetry. Alexander writes:

“The poems in this book pay tribute to the poets being celebrated by adopting their style, extending their ideas, and offering gratitude to their wisdom and inspiration.”

Following this description then, it should not surprise the reader that the poems in the book are organized into three parts.

Part I, titled “Got Style?”, offers us six poems, written in the styles of Naomi Shihab Nye, Robert Frost, e. e. cummings, Bashō, Nikki Giovanni, and Langston Hughes. It is a great idea indeed to start with a style focus like this; these poets have particularly distinct styles, and the six poems honoring them manage to showcase to the young reader what possibilities exist for poetic form.

Part II, titled “In Your Shoes”, celebrates Walter Dean Myers, Emily Dickinson, Terrance Hayes, Billy Collins, Pablo Neruda, Judith Wright, and Mary Oliver with seven poems that explore themes and contexts that come directly from these poets’ own works.

Part III, titled “Thank You”, includes seven more poems, this time explicitly thanking and celebrating Gwendolyn Brooks, Sandra Cisneros, William Carlos Williams, Okot p’Bitek, Chief Dan George, Rumi, and Maya Angelou.

The book ends with a list of biographies of the twenty poets celebrated in it, so the curious reader can learn a bit more about these poets if desired. But of course the really curious bunnies will also want to check out poems by these poets. To that end, most of the links I provided above to the poets go to the Poetry Foundation page on them where you can find at least a couple sample poems.

All twenty poems in Out Of Wonder are accessible to young readers, but they do not underestimate them. Each poem stands on its own, with its distinct style and voice. Alexander’s “Jazz Jive Jam” celebrating Langston Hughes dances even!

These are all really appealing poems. For example Marjory Wentworth’s “In Every Season” celebrating Robert Frost leaves resonances in one’s palate which complement the experience of reading his “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”. Chris Colderley’s “For Our Children’s Children” celebrating Chief Dan George is striking in its simplicity–here is an excerpt:

Let the shadows

of drifting clouds

warm your cheek

and whisper softly:

Share the earth

with all creatures.

Love them, and they

will love you back.

Kwame Alexander’s “I Like Your” celebrates e. e. cummings in a style that reflects the latter’s very own–here is the beginning of this lovely poem:

I like my shoes when they are with

your shoes. Mostly the comes. Leastly

the goes. I carry your footsteps(onetwothreefour)

in between today(...)tomorrow.

Each and every one of these poems is a joy to read. And each is accompanied by beautiful illustrations by the talented Ekua Jolmes. Most poems thus get a full two-page spread and the illustrations are as distinct and striking as the poems themselves.

This is not a book to read from cover to cover in one sitting. Read one poem, look at the beautiful illustrations accompanying it, check the bio of the poet celebrated by the poem that is provided at the back of the book, and then finally, if you have the time, go find some poems by the same poet to see if you will find a new favorite of your own.

***

If you would like to know a bit more about the book, you should probably know that it has its own Wikipedia page! And you can also view the book trailer on Youtube: