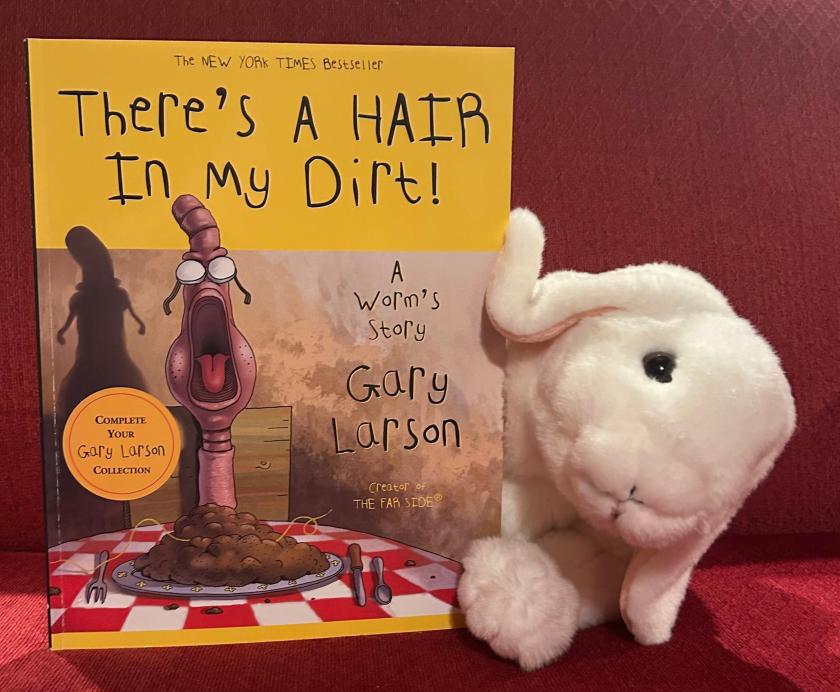

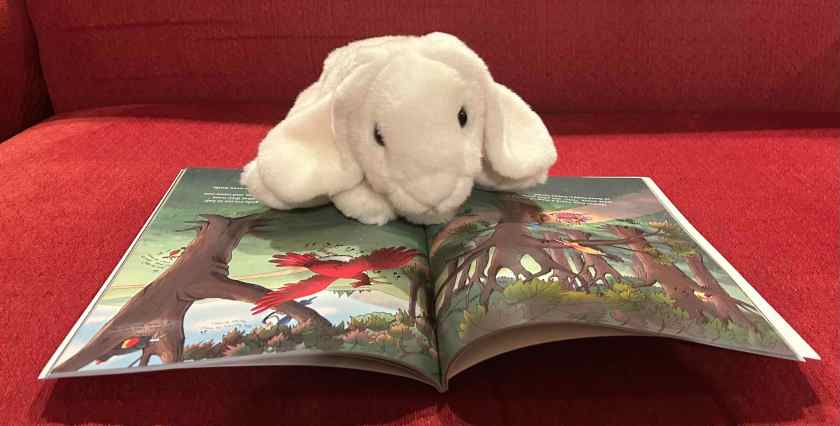

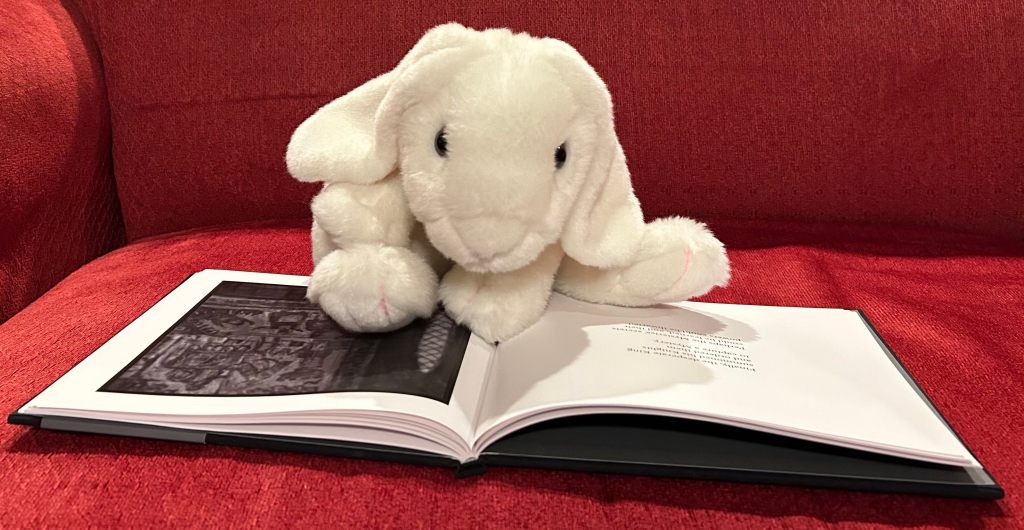

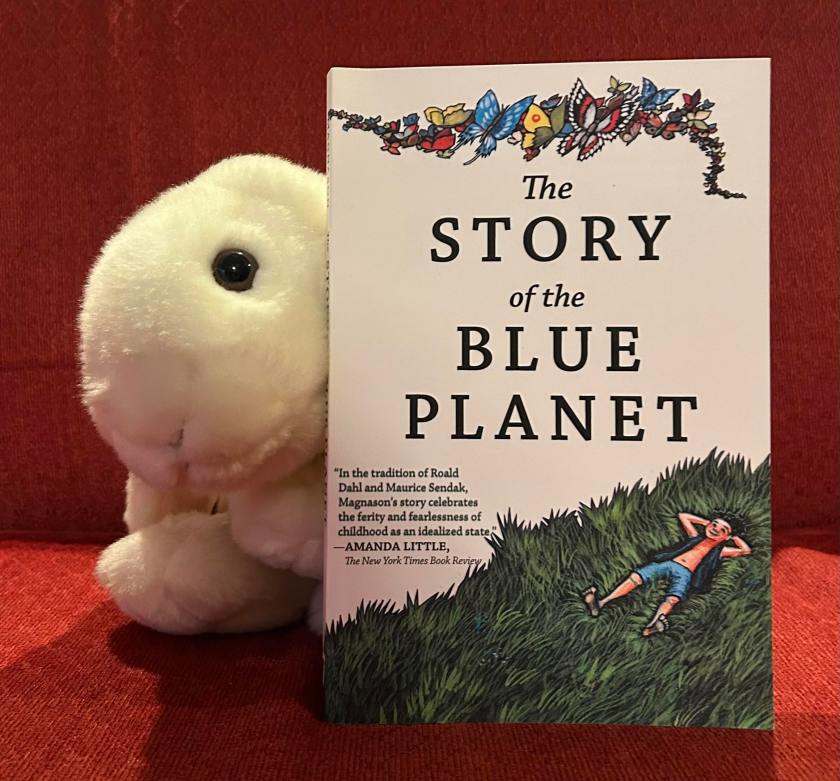

Today Marshmallow reviews The Story of the Blue Planet, written in Icelandic by Andri Snær Magnason in 2000, illustrated by Áslaug Jónsdóttir, and translated into English in 2012 by Julian Meldon D’Arcy.

Marshmallow’s Quick Take: If you like books that are interesting, thought-provoking, yet quick and easy to read, then this is the book for you!

Marshmallow’s Summary (with Spoilers): The story starts off with a simple introduction to the Blue Planet. It’s a world that the narrator describes as un-interesting to anyone who wants to study planets. It is pretty similar to our own planet with beautiful waterfalls, oceans, forests, islands, and everything else we have here on Earth. The key difference between our world and the Blue Planet is that the Blue Planet is only inhabited by children. The children live a life that is somewhat like the lives of hunter-gatherers from the past of Earth. They hunt, gather, and eat what they need and—in this manner—their world is a heavenly paradise full of children who play most of the day.

However, this all changes when Gleesome Goodday arrives. His spaceship falls from the sky after spelling out a question of whether or not they want to have real fun. When the spaceship crashes though, Brimir and Hulda are the first to find it and see the emerging silhouette of Goodday as the coming of a space monster. They run away, but find upon their return that Goodday has become very popular among the children despite the fact that he is the first adult to have existed on the Blue Planet.

Goodday gives all children business cards that advertise his various, bizarre businesses and claims that he can grant their deepest desire, which is to have fun. However, the children already have almost constant fun. Goodday refuses to believe this though, dismissing their activities as too boring. He offers to make them fly because, as he points out, almost everyone has had a dream of flying at some point. Every year, butterflies emerge from hibernation in caves in the mountains and fly around the world, following the sun for a day. Then they return to their homes and sleep for the rest of the year. Goodday, who they name Jolly Goodday, sucks up some butterfly dust using his special vacuum and then sprinkles it on the children. This magically allows them to fly while the sun is up.

Unfortunately, this story soon illustrates the impacts of greed, as the children continue to make demands for more (though these demands are often inspired by Goodday himself). Though this book is set in a very unrealistic world, it shows the very real impacts of some very real human instincts.

Marshmallow’s Review: I found The Story of the Blue Planet to be a very fascinating book. It is very short and very simplistically written, so any and all bunnies of any and all ages can read it and understand it. It took me around an hour (and this is a bit of an overestimation) to read this book, so it is not very long. Yet, it sticks with you a bit because the story is so familiar and so foreign at the same time.

On the surface, The Story of the Blue Planet is a story about greed and selfishness told through the vehicle of the fable. But I think it is also about forgiveness and human understanding … for reasons I don’t think I should explain or can explain without spoiling the ending. I think it also teaches empathy and compassion in the face of compelling complacency. I am not sure how such a simplistic book can cover so much thematic ground, but somehow Magnason did it! I would highly recommend reading this to all!

[If you are curious about it, here is the first of a series of YouTube videos where the author reads the book from cover to cover.]

Marshmallow’s Rating: 95%.